Read more ...

Répliques

"In the theatrical sense, a « Répliques » is at once an appropriation, an up-dating and a riposte.

Seven invited artists will play the game of replication and bring their contemporary response to the masterpieces of the Japanese collections of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, adding a few lines to the History of Japonism of which the School has been the theater.

Echoing a selection of 24 Japanese prints or accordion books chosen from the Tronquois collection of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Laury Denoyes, Morgane Ely, Alice Narcy, Adoka Niitsu, Mariia Silchenko, Lucile Soussan and Alžbětka Wolfová respond with a contemporary work.

Based on an idea by Clélia Zernik, professor at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, with Anne-Marie Garcia, conservator, responsible for the collections of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Rym Ferroukhi, Pétronille Mallié and Soukaïna Jamai, scenographers and Alice Narcy, curator in residence.

Masterpieces from Japanese collections: Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, Kunisada 1er, Egawa Tomekichi "*

Seven invited artists will play the game of replication and bring their contemporary response to the masterpieces of the Japanese collections of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, adding a few lines to the History of Japonism of which the School has been the theater.

Echoing a selection of 24 Japanese prints or accordion books chosen from the Tronquois collection of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Laury Denoyes, Morgane Ely, Alice Narcy, Adoka Niitsu, Mariia Silchenko, Lucile Soussan and Alžbětka Wolfová respond with a contemporary work.

Based on an idea by Clélia Zernik, professor at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, with Anne-Marie Garcia, conservator, responsible for the collections of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Rym Ferroukhi, Pétronille Mallié and Soukaïna Jamai, scenographers and Alice Narcy, curator in residence.

Masterpieces from Japanese collections: Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, Kunisada 1er, Egawa Tomekichi "*

(*Text from the exhibition "Le Théâtre des Expositions « Répliques Japonisme »" at Palais des Beaux-Arts de Paris, France, 2021)

Modern Makeup Mirror of Today

Ukiyo-e: A History of Technique and ImageUkiyo-e is media. The images that recorded the customs of the Edo period drifted, floated, crossed the seas, and transformed the course of Western art. Living and working in France, I had long wished to create a work that explores ukiyo-e as a reproducible image - as reproducible art.

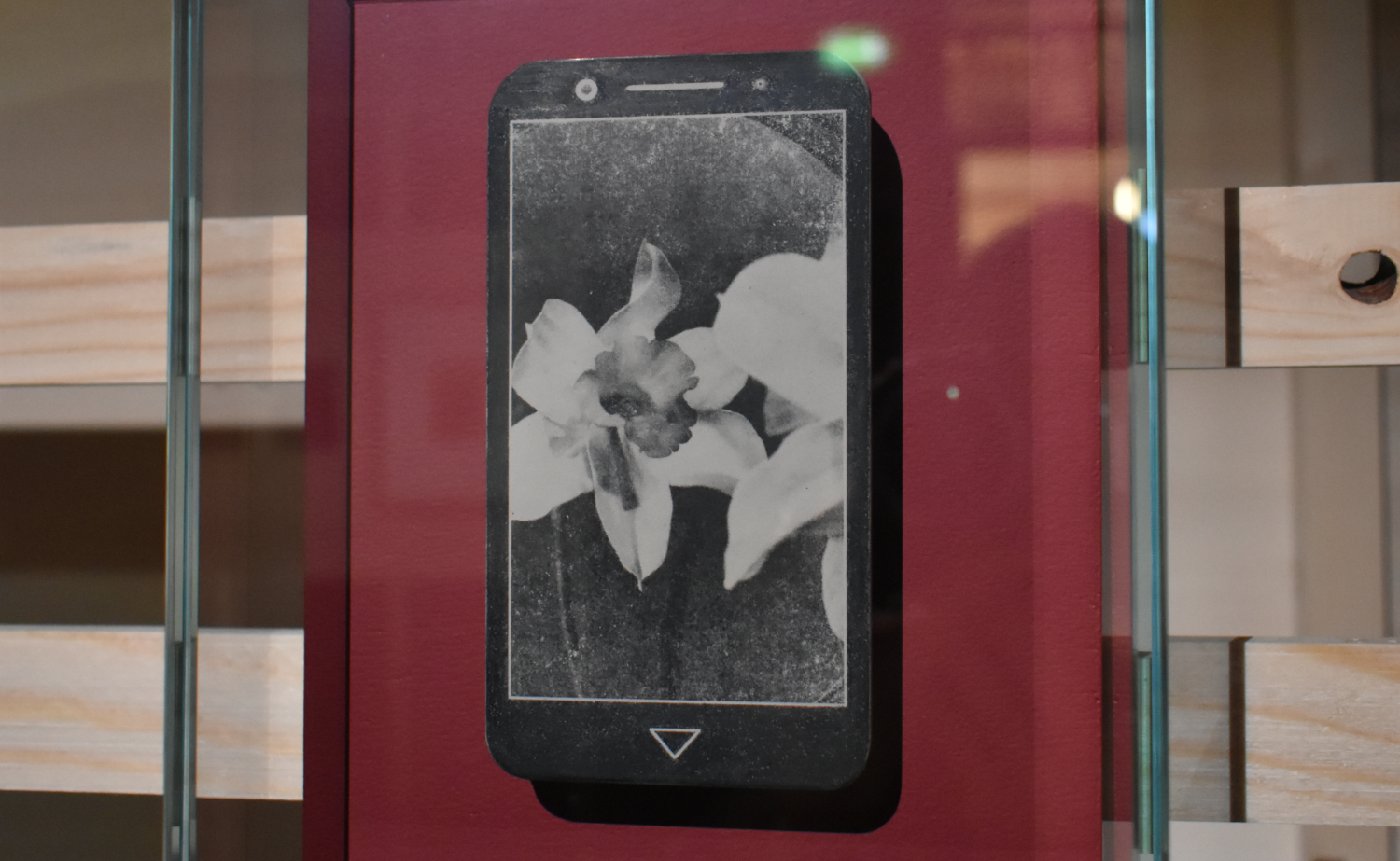

Ukiyo-e encompasses a wide variety of themes, including portraits of beautiful women gazing into mirrors. Among them, Imafū Kesho Kagami (“Modern Makeup Mirror”) by the first Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865) stands out for its fascinating composition: a hand mirror treated as though it were a screen displaying the image of a woman applying makeup.

During the Edo period, cosmetic culture flourished, and even women of commoner status began to wear makeup. Depending on one’s social status—whether single or married, a courtesan or a geisha—specific codes of hairstyle and makeup existed. For example, married women shaved their eyebrows and blackened their teeth with ohaguro. The series Imafū Kesho Kagami depicts this culture with remarkable fidelity and even includes an advertisement for Senjakō, a popular white powder of the time, making the print function as a true medium comparable to today’s social networks.

In 2021, when I had the opportunity to participate in an exhibition at the Beaux-Arts de Paris that brought the school’s collection into dialogue with works by its students and faculty, I consulted the database and discovered that the Imafū Kesho Kagami series was part of the collection.

Selfie culture—applying makeup while using a smartphone as a mirror, adding filters, and circulating replicated images across social networks—can be seen as a contemporary version of Imafū Kesho Kagami. I began to imagine a work connecting the women of Edo reflected in the mirror with today’s mirror selfies.

Narcissus: Identity and Media Technology

The social phenomenon in which one values one’s own image on social networks—selfies—more than reality is often compared to the Greek myth of Narcissus. The flower “narcissus,” whose name derives from the Greek narkō (“numbness,” referring to the poison in its bulb), is intimately tied to this myth. The psychologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) referred to Narcissus when defining narcissistic personality disorder, which he called “narcissism.”

Today, in the vast ocean of social networks, perhaps we are not enamored with ourselves but rather numbed by the “manufactured images” reflected back at us through the technological mirrors of a vast capitalist system. The number of likes and shares may resemble Echo from Greek mythology.

The Artificial Narcissus Flower: The Eternity of the Ephemeral Narcissus

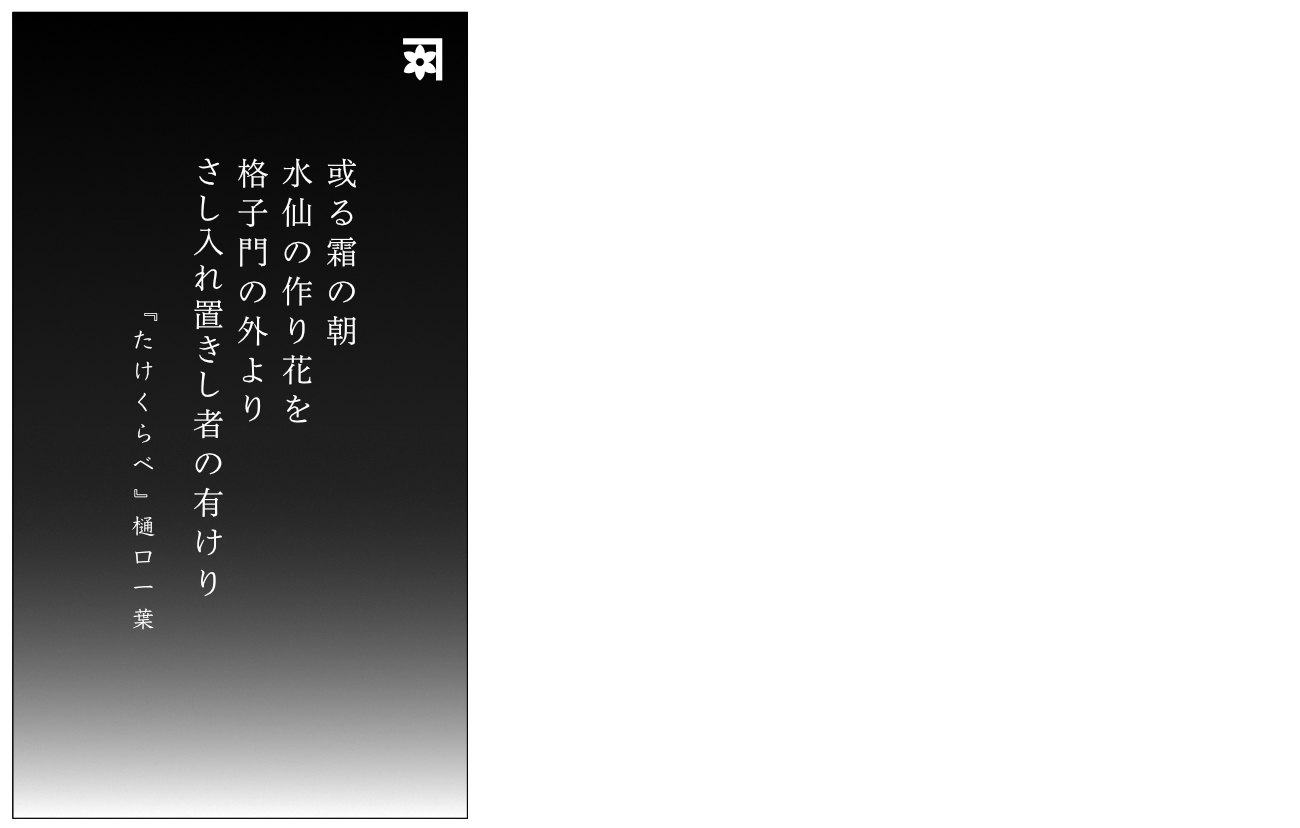

“On a frosty morning, someone inserted an artificial narcissus flower through the lattice gate from outside.” — Higuchi Ichiyō (1872–1896), Takekurabe (1893)

To symbolize an eternal farewell, Higuchi Ichiyō chose the narcissus flower.

Midori, a fourteen-year-old girl destined to become a geisha like her older sister, a courtesan of the Yoshiwara district, and Shinnyo, the son of a temple, grew up together. Yet as adolescents who have begun to feel new awareness toward each other, they must move toward completely different futures, each dictated by their predetermined paths.

One of the prints in Imafū Kesho Kagami, depicting a geisha adjusting her hair in a black hand mirror, overlaps symbolically with the scene in which Midori changes her hairstyle to the shimidamage, the hairstyle of an adult woman. Changing her hairstyle signifies that her preparation to become a courtesan has begun.

On a winter morning, Midori finds an artificial narcissus flower slipped into the gate. “Not knowing who had left it, she placed it in a small vase on the shelf and admired its quiet and pure form. And without really hearing it, she learned that the next day was the day Shinnyo was to depart for the monastic school.”

This final scene—stating only that Shinnyo has left—leaves the reader’s imagination to fill in the silence, making the moment all the more poignant. Who placed the flower there? Was it Shinnyo, as a farewell token for Midori? One hopes so. One feels it must be so. And one wonders about the meaning of choosing an artificial flower instead of a fresh one that would quickly wilt. Resonating in this image are Buddhist artificial flowers, kuge (offering flowers), and the spirit of ikebana: the profound wish to make eternal what is, by nature, ephemeral.

Higuchi Ichiyō, the author of Takekurabe, chose as her subjects those living at the margins of society, especially women forced to confront the rapid societal changes of the Meiji era. She herself suffered poverty and discrimination and, despite her short life—dying at twenty-four—left behind masterpieces.

A flower native to the Mediterranean Sea that crossed the Silk Road to reach Japan, Narcissus called Suisen (水仙, lit.legendary aquatic immortal from Chinese folklore) is a symbol of purity, modeste and overcoming adversity, and prayer in that it keeps its head down and blooms even in the snow, and is also a symbol of fighting illness and recovery from a disaster like earthquake and Tsunami. The image of the Narcissus is continually reflected in the "Infinity Mirror," with various myths and stories intertwined in the east and west, ancient and modern.

The Metamorphosis of Narcissus

Another version, “Mirror #Narcisse [liked by echo]”, was created for the 2022 exhibition “The 1900 Foundation of Joshibi University of Art and Design: A History of Higher Art Education for Women in Japan” and shown at Palazzo Bembo, Ecc-Italy, in Venice. Joshibi University of Art and Design, Niitsu’s alma mater, was founded in an era when women were not permitted to enter art universities, with the mission of supporting women’s independence. The school once had a department dedicated to artificial flowers, and its emblem is the Yata no Kagami, a sacred mirror symbolizing self-examination.

Adoka Niitsu

Remerciements :

I would like to thank Noriko Mitsuhashi, Maki Toshima and Alice Narcy for thoughtful discussion on the early stages of this work. Laurent Lafont-Battesti, Co-Traduction for the text from "Takekurabe(lit. 'Comparing heights')" by Ichiyo Higuchi in French.

I would like to thank Noriko Mitsuhashi, Maki Toshima and Alice Narcy for thoughtful discussion on the early stages of this work. Laurent Lafont-Battesti, Co-Traduction for the text from "Takekurabe(lit. 'Comparing heights')" by Ichiyo Higuchi in French.